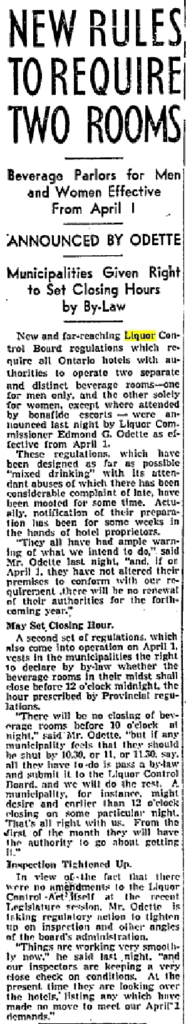

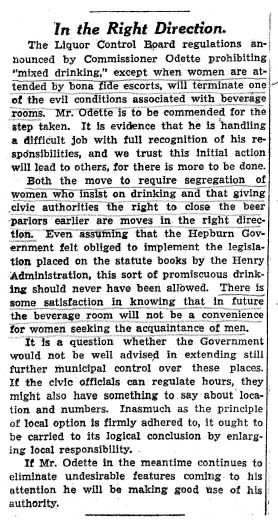

The presence of women within drinking establishments along with unmarried men, prompted a moral outcry against the possible sexual impropriety inspired by “mixed” drinking within male beverage rooms in the mid 1930s (The Globe September 18th 1934, “Trustee Observes Girls Being Brought Out of Beer Rooms”; The Globe, March 6th 1935, “50 Girls seen Drinking By Minister”). In response, the LCBO drafted new regulations in 1937 that required licenced establishments to have “two separate and distinct beverage rooms – one for men only, and the other solely for women, except where attended by bona fide escorts” (The Globe March 29, 1937, “Liquor Board to Curb Mixed Drinking in Ontario Hotels, New Rules to Require Two Rooms”).

Women could also drink within their homes, yet in the Board’s early years, even there some female drinkers were the subject of gossip and public criticism. The Globe reported on women purchasers on the LCBO’s opening day in 1927 as if they were spectacles for public consumption. Articles were critical of women who “wheeled baby carriages” when making their purchases, or were assertive of their right to drink – openly questioning their ability to both drink and be effective mothers (The Globe June 2, 1927 “They Line Up Quickly to Get Their Liquor Once Stores Are Open”). Further, discourses surrounding alcoholism and motherhood in the late 1930s expressed fears over a scientifically underdeveloped and fear-based understanding of what would later become known as fetal alcohol syndrome: a WCTU speaker expressed “science claims that alcoholic mothers give to the world either a prostitute or a delinquent, when she does not give an epileptic, an idiot or lunatic” (Convention of the WCTU, 1937: 32-34 cited in Marquis 2004: 317).

Many women during the Board’s early years also avoided retaining a permit of their own, for fear of being stigmatized, again increasing the degree to which female gender performances concerning alcohol were mediated by male figures within their lives. When it came to Board policy, the identity of women’s husbands or fathers was integrated into the purchase process, as the occupations and sometimes names of these men were included on female permits acting as the lenses through which cases of misspending and overindulgence were viewed.

Unlike men’s clubs and legions, which served as a means for men to resist Board control over their drinking spaces, women’s clubs were denied this privilege. As Heron (2005: 20) notes, this “issue blew up first in 1935 when the Germaine Club, which had always had a mixed membership, was ordered to stop serving beer to women”; the Board held firm to its decision, disallowing even women in uniform and the gender exclusive woman’s auxiliary equivalents of male clubs which had no trouble obtaining a licence (Heron 2005: 20).

<< The Return of Drinking Establishments 1934 Ladies and Escorts >>